Flexor tendon pulley injuries occur most commonly in rock climbers, accounting for 27% of all finger injuries (Schoffl et al 2003). This post will revisit the anatomy, and look at the causes and symptoms, and then discuss treatment methods.

Please note: any finger injury sustained by anyone under the age of 18 should be seen by a professional due to the risk of more severe injury such as an epiphyseal plate injury

Please note: any finger injury sustained by anyone under the age of 18 should be seen by a professional due to the risk of more severe injury such as an epiphyseal plate injury

Anatomy

Understanding the anatomy within the fingers is key to understanding the injuries to the pulley system, therefore, I will cover some old ground of the finger anatomy.

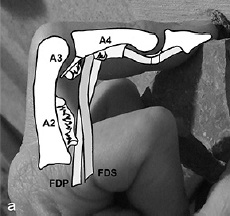

Firstly, the tendons involved in the fingers are the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) and the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS). These are both involved in flexing the finger joints.

This is worthy of note, as the A2 pulley contains the both these tendons, whereas the A4 pulley only contains the tendon of the FDP as the FDS splits and inserts to the lateral sides of the A4 pulley (see image below).

This means more force is exerted on the A2 pulley than the A4 (hence why climbers most commonly injure the A2 pulley)

|

| This image shows how the FDS splits and inserts laterally to the joints, therefore not passing through the A4 pulley |

|

| Ligaments of the finger |

This means that the A2 is 1.5 - 2 times more likely to be injured than the A4 pulley.

(N.B. The A2 pulley is found near the base of your finger)

The ring finger is the predominantly injured finger, due to the middle finger being supported by relatively strong and long fingers, whereas the ring finger only has a strong, long finger on one side, and flanked by the relatively weak little finger, meaning it is more susceptible to injury.

Check this out for real-life anatomy of pulleys on a cadaver

(Note: not for the faint hearted!)

Causes

Causes of a pulley injury can be from:

- Foot slip etc when crimping a hold

- Dynamic pull from a small edge

- Dynamic move to a small edge

- One finger pockets

- Repetitive strain

Severity of the injury

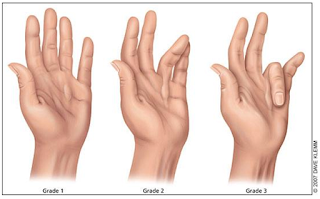

With a pulley injury, there are degrees of severity of the injury, graded from I to III:

With a Grade III, you will be very limited in what you can do, whereas a Grade I there will be more flexibility.

With a pulley injury, there are degrees of severity of the injury, graded from I to III:

- Minor sprain to the ligaments and pulley

- Partial tear to the pulley

- Complete rupture of the pulley

With a Grade III, you will be very limited in what you can do, whereas a Grade I there will be more flexibility.

Symptoms

Symptoms of a pulley rupture may consist of:

- A loud, audible pop (normally for a complete rupture) accompanied with pain (See above video)

- Swelling at the base of the finger

- Bowstringing of the tendon visible or on palpation

- Limited mobility of the finger

- A small audible pop

- Sudden onset of pain after grabbing a hold

- Swelling

- Limited mobility of the joint

A partial tear of a pulley could alternatively be misdiagnosed as a "flexor unit strain", also known as a lumbrical tear (detailed in this post), or vice versa.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a pulley injury is normally based on the subjective history, and clinical examination (e.g. bowstringing). Ultrasound can be used to confirm bowstringing (bowstringing only occurs in complete ruptures).

|

| Copyright Hauger et al 2000 |

MRI can show an A2 injury, but is not commonly used.

| ||

|

Treatment

In the past, it was encouraged for a surgical approach to repair pulley ruptures. However, nowadays, a conservative approach has been found to be equally effective.

Rest

Climbing should be stopped only for the period in which the joint is inflamed, and it is recommended this period should be around 1-3 weeks.

Obviously this depends on the level of injury, as a complete rupture will require longer time off, whereas a partial tear will require less.

Once the joint can be moved through it's full range of movement pain-free, then this is a good indication that you may be able to start gently climbing again.

Rest also includes sleeping well and having a healthy diet, as these often aid the recovery process.

I generally find this “rest” period can be used to train other areas, such as those antagonists you've never got round to training, or that core strength that you just don't have time for at the wall.....!

Ice/Cold Water Therapy

Again, a principle from a previous post on acute injury management, icing the affected area will help promote healing and reduce inflammation

Within this is also the idea of contrast baths. However, there is limited research that they work, and no set prescribed pattern of time frame or temperatures.Google them, try them, make your own decision!

You can also try and use this clever device by BananaFinger to ice the finger.

Stretching and massage

Stretching the affected joint helps optimise the alignment of the healing fibres. A stretch needs to maintained for at least 30 seconds to have any affect. Warming up prior to stretching is recommended.

Massaging the affected area can also optimise fibre alignment and break down any scar tissue forming, but needs to be quite vigorous and can be quite painful in order to have any effect.

Recovery Aids

|

| Metolius Grip Saver |

|

| Exercise Balls (e.g. Theraband) |

They are also useful tools for warming up.

I am particular keen on the Metolius Grip Saver as you can use the ball to work the extensors to your fingers as well as flexing them, ensuring an equal work out to the muscle groups. (See this post on hand and finger exercises)

Within these aids is "TheraPutty", or glorified PlayDough. Use it in the same way you use the hand exercise ball.

Some people also use those Chinese stress balls, the heavy metal ones you rotate in your hands. These are good too.

It's about finding what best works for you.

Taping

Several techniques can be utilised for taping of pulley injuries. The idea of taping is to reduce the acute angle of the flexor tendons, as shown in one of the images below.

The tape takes approximately 10% of the strain from the pulley system, and can allow climbing with support to the injured finger, but remember it doesn't cure the injury, and only lasts a short period of time before the tape slackens off.

Tape will also not prevent pulley injuries, nor support the injury once nearly healed (however is not going to harm the finger in any way, apart from giving you a false sense of security that the injury has healed when it may not have, or be stronger than it is).

There are two techniques, the main one being H-tape, shown below:

H-Tape

Watch the video below, or here's a link to a picture guide of how to H-tape

Other technique:

This technique is offered by Schwiezer 2012

(However, personally, I think the H-Tape has a better practical use and changes the angle of the tendons more effectively and limits the finger movement less)

Within these aids is "TheraPutty", or glorified PlayDough. Use it in the same way you use the hand exercise ball.

Some people also use those Chinese stress balls, the heavy metal ones you rotate in your hands. These are good too.

It's about finding what best works for you.

Taping

Several techniques can be utilised for taping of pulley injuries. The idea of taping is to reduce the acute angle of the flexor tendons, as shown in one of the images below.

The tape takes approximately 10% of the strain from the pulley system, and can allow climbing with support to the injured finger, but remember it doesn't cure the injury, and only lasts a short period of time before the tape slackens off.

Tape will also not prevent pulley injuries, nor support the injury once nearly healed (however is not going to harm the finger in any way, apart from giving you a false sense of security that the injury has healed when it may not have, or be stronger than it is).

There are two techniques, the main one being H-tape, shown below:

H-Tape

Watch the video below, or here's a link to a picture guide of how to H-tape

|

| The shape of the H-Tape |

This technique is offered by Schwiezer 2012

(However, personally, I think the H-Tape has a better practical use and changes the angle of the tendons more effectively and limits the finger movement less)

| ||||||||

| Showing a different taping method, and how the tape is designed to re-orientate the flexor tendons | . | Copyright Schweizer |

Schweizer tested two kinds of taping on

16 fingers during the typical crimp grip position.

Taping over the A2 pulley decreased bowstringing by 2.8% and absorbed

11% of the force of bowstringing. Taping over the distal end of the

proximal phalanx decreased bowstringing by 22% and absorbed 12% of

the total force. Circular taping is minimally effective in relieving

force on the A2 pulley.

Drugs

As with any injury, the use of anti-inflammatories and pain killers may help, however remember that in the initial stages of the injury, the inflammation is part of the natural healing process, and pain killers stop pain. Pain means something isn't right and to stop, so if yo can't feel the pain, it removes the ability for you to listen to your body.

This list is by no means exhaustive of all the techniques out there to aid recovery from a pulley injury.

Returning to Climbing

When returning to rock or plastic, it is advised to start off easy, and slowly and gradually build up your sessions, intensity and grade until you know the injury has returned to the optimal strength.

You may find it easier to climb with open hand grips at this stage, and therefore climb harder than otherwise thought, but it only takes one hold for you to have to crimp to succeed, and you're back to square one.

It's important to listen to your body, especially during these phase, as it is so easy to re-injure when that amazing looking problem entices you in, just for a quick go. We are all guilty of this one!

Preventative measures

Taping, however, to prevent a pulley injury doesn't work, as it has been shown that the tape is not strong enough to absorb the forces involved in causing injuries. (Warme and Brooks 2000)

Check out Chockstone.org for some more advise and info on taping.

The usual basis of a proper warm up and easy climbing is an obvious, yet poorly practiced, preventative measure.

If it doesn't feel good, don't do it!

Changing your technique and style, and having a greater awareness of where your body is in space will mean you are less likely to have a foot slip, or need for dynamic moves to holds, therefore reducing the likelihood of injury.

Avoid projects way beyond your current capabilities

Variety is the spice of life - vary the duration, intensity, holds, style, angle and training tools used when climbing.

Also, change your technique to utilise open handed grip instead of over-crimping every hold will reduce the force placed on the pulley system

As a beginner, remember that your muscles will adapt very quickily to an increase in workload, but the ligaments, tendons and pulleys take much longer to adapt, therefore making them more prone to injury. The key to this - progress your climbing in a sensible, progressive manner.

And finally, ensuring you've had enough sleep, food, water etc to ensure a productive climbing experience!

Hope this helps! Any question, feel free to ask!

Obviously every case is individual, and this is merely for reference and information. If you have an injury - get it checked out by a professional!

Check out ClimbingStrong.com for an interesting DIY method of rehab

References

Hochholzer T, Schoffl VR 2006 One Move Too Many. Lochner-Verlag, Germany

Schwiezer A 2012 Sport climbing from a medical point of view. Swiss Medical Weekly 142: w13688

Schoffl V, Hochholzer T, Winkelmann HP, Strecker W 2003 Pulley injuries in rock climbers. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 14: 94-100

Chapman G 2008 Finger injuries and treatment . Rock and Run

Macleod D 2010 Pulley injuries article. Online Climbing Coach

Schweizer A 2001 Biomechanical Properties of the Crimp Grip Position in Rock Climbers. Journal of Biomechanics 34:217 - 223

Schoffl VR, Schoffl I 2007 Finger pain in rock climbers: reaching the right differential diagnosis and therapy. Journal of Sports Medicine Physical Fitness 47:70-78

Hauger O, Chung CB, Lektrakul N, Botte MJ, Trudell D, Boutin RD, Resnick D 2000 Pulley System in the Fingers: Normal Anatomy and Simulated Lesions in Cadavers at MR Imaging, CT, and US with and without Contrast Material Distention of the Tendon Sheath. Radiology 217(1): 201-21

This list is by no means exhaustive of all the techniques out there to aid recovery from a pulley injury.

Returning to Climbing

When returning to rock or plastic, it is advised to start off easy, and slowly and gradually build up your sessions, intensity and grade until you know the injury has returned to the optimal strength.

You may find it easier to climb with open hand grips at this stage, and therefore climb harder than otherwise thought, but it only takes one hold for you to have to crimp to succeed, and you're back to square one.

It's important to listen to your body, especially during these phase, as it is so easy to re-injure when that amazing looking problem entices you in, just for a quick go. We are all guilty of this one!

Preventative measures

Taping, however, to prevent a pulley injury doesn't work, as it has been shown that the tape is not strong enough to absorb the forces involved in causing injuries. (Warme and Brooks 2000)

Check out Chockstone.org for some more advise and info on taping.

The usual basis of a proper warm up and easy climbing is an obvious, yet poorly practiced, preventative measure.

If it doesn't feel good, don't do it!

Changing your technique and style, and having a greater awareness of where your body is in space will mean you are less likely to have a foot slip, or need for dynamic moves to holds, therefore reducing the likelihood of injury.

Avoid projects way beyond your current capabilities

Variety is the spice of life - vary the duration, intensity, holds, style, angle and training tools used when climbing.

Also, change your technique to utilise open handed grip instead of over-crimping every hold will reduce the force placed on the pulley system

|

| Diagram to represent the forces exerted using crimp vs open handed Copyright Schweizer |

As a beginner, remember that your muscles will adapt very quickily to an increase in workload, but the ligaments, tendons and pulleys take much longer to adapt, therefore making them more prone to injury. The key to this - progress your climbing in a sensible, progressive manner.

And finally, ensuring you've had enough sleep, food, water etc to ensure a productive climbing experience!

Hope this helps! Any question, feel free to ask!

Obviously every case is individual, and this is merely for reference and information. If you have an injury - get it checked out by a professional!

Check out ClimbingStrong.com for an interesting DIY method of rehab

References

Hochholzer T, Schoffl VR 2006 One Move Too Many. Lochner-Verlag, Germany

Schwiezer A 2012 Sport climbing from a medical point of view. Swiss Medical Weekly 142: w13688

Schoffl V, Hochholzer T, Winkelmann HP, Strecker W 2003 Pulley injuries in rock climbers. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 14: 94-100

Chapman G 2008 Finger injuries and treatment . Rock and Run

Macleod D 2010 Pulley injuries article. Online Climbing Coach

Schweizer A 2001 Biomechanical Properties of the Crimp Grip Position in Rock Climbers. Journal of Biomechanics 34:217 - 223

Schoffl VR, Schoffl I 2007 Finger pain in rock climbers: reaching the right differential diagnosis and therapy. Journal of Sports Medicine Physical Fitness 47:70-78

Hauger O, Chung CB, Lektrakul N, Botte MJ, Trudell D, Boutin RD, Resnick D 2000 Pulley System in the Fingers: Normal Anatomy and Simulated Lesions in Cadavers at MR Imaging, CT, and US with and without Contrast Material Distention of the Tendon Sheath. Radiology 217(1): 201-21

Schwiezer A 2000 Biomechanical effectiveness of taping the A2 pulley in rock climbers. The Journal of Hand

Surgery: British & European Volume 25(1): 102-107